Naresh Fernandes, addressing participants at Intellecap’s “The Future of the Urban Poor: A Searchlight Convening” supported by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Good evening and welcome to Bombay. This is a city in which I’ve lived for much of my life and there are few places in which I feel more at home than right here, in Bandra. My family’s roots in this neighbourhood go back at least two hundred years. At the other end of this stretch of seafront is St Andrew’s Church, where five generations of my family are buried. My grandfather used to farm a small plot of land not so far from here, and, over the past century, my family has witnessed the city springing up around it. Recently, I’ve been working on a book I’m tentatively calling Hill Road Stories, named after Bandra’s longest street, in which I’m trying to describe how Bandra came to be absorbed by the big city.

This spot in which we’re meeting (Taj Lands End hotel, Band Stand) holds warm memories for me. When I was a child, this was an overgrown hill with the remnants of an old Portuguese fort. During our school holidays, we’d ride our bicycles up here and play act at fighting pirates amidst the ruins. Bandra was in the possession of the Jesuits from the early 1600s, and the tax revenues they gained from my ancestors allowed them to entertain their guests quite lavishly. In 1675, a young British doctor named John Fryer stopped in to visit the Jesuits. He writes that they showed him “great civility”, offering him fine fruit and wine, “diverting us with instrumental and vocal music”. Later in the day, they even staged a mock naval battle for him in the bay out front. So it’s evident that we in Bombay have a long tradition of showing our guests a good time.

About 15 years ago, after a long court battle, this hotel was allowed to come up over the remnants of the fort and only a small section of the battlements remain now. If you walk down to the water’s edge, you’ll see an old stone plaque bearing the date 1640. But you won’t actually be able to walk all the way out onto the parapet. It’s been blocked off for security reasons. Evidently, if you try to take a deep breath of the sea air at that spot, you could pose a grave threat to the structural stability of the Bandra-Worli Sealink, which links Bandra to the mainland.

This hotel offers a fabulous vantage point from which to observe Bombay’s metamorphosis in the new millennium: it’s built atop a 17th-century fort and looks out on the bridge that many people believe symbolises Bombay’s potential to take on the world in the 21st century.

Like so much else in this city, though, that bridge, to me is a sign of how much we in India have been getting wrong, ever since we began our policy of structural adjustment in the early 1990s. The bridge cost six times more than expected and took more than ten years to complete – that’s five years longer than they expected. When you drive off at the Worli side, there’s a large sign that says South Bombay – but weirdly, the direction it indicates is actually north. To get to South Bombay off this bridge, you actually have to drive about 300 metres north and then take a U turn before you’re set in the right direction.

But it’s more than the awkward engineering and the delays that made this a bad use of money. Of the 14 million people who live in the city, 6.9 million people take the train. Only 37,500 vehicles actually use this bridge every workday. The sealink was planned as a public-private partnership and was supposed to demonstrate how Bombay’s residents would actually be willing to pay for infrastructure they used. Think again. When they bridge opened, they actually had to reduce the toll, because it was so poorly used.

There’s another delusion involved. Many of Bombay’s newly affluent people that users of public transport are subsidised. When you do the maths, it turns out that isn’t quite true. While the average passenger on the sealink pays Rs 25.25 per journey, the average first-class ticket holder on the railways pays Rs 54. It turns out that we’re actually subsidising the inefficient car-users. Despite the shaky assumptions of this project, the state government is still proceeding with its plan to extend the sealink all the way down to the very tip of the city.

While we’re still up here on the hill, let’s also turn our eyes east, to the neighbourhood of Dharavi, where you’ll be headed over the next few days. While some Bombayites have adopted the Sealink as a symbol of everything they believe is right with the city, I must confess that I’m quite astonished by how many others seem to believe that Dharavi is a shining example of the city’s potential. That’s a process that’s greatly accelerated with the success of the film Slumdog Millionaire. In fact, when Barack Obama visited Bombay a few months ago, he made it a point to praise the people living in the “winding alleys of Dharavi” for their optimism and determination.

New urban studies jargon now refers to Dharavi as “an informal city” that has been created by the boundless enterprise of its residents. Almost every news report about Dharavi informs readers that its residents produce several hundred million dollars worth of goods each year – some estimates suggest a figure of $500 million or $600 million. As a corollary, this school of opinion believes that informal settlements like Dharavi and the hundreds of others around Bombay should be left undisturbed, so that they can continue to keep displaying boundless enterprise and keep being productive citizens. There’s also an ecological edge to this argument. Dharavi’s residents are praised for how efficiently they use scarce space and resources. Academics who celebrate Dharavi say that the world can’t really afford to live any other way.

Don’t get me wrong. I entirely support the right of poor to live and work in the city. In fact, I believe that we must do a great deal more to ensure that they get a fair deal in Bombay. But to me, this fetishisation of Dharavi makes a virtue out of very dire necessity. Besides, it’s tinged wth a condescending, neo-liberal lining. As I see it, this rhetoric implies that Dharavi residents should be allowed to live there mainly because they’re contributing to our great economic machine – not just because they, as citizens, have the same rights to the city as we do.

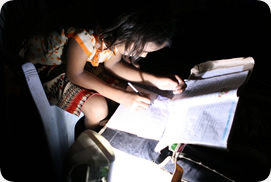

When you visit Dharavi, ask its residents about the struggle they face getting water in the morning, about how many people are packed together with them in their homes, about the rats that nibble at their toes each night and then reconsider the alleged magic of Dharavi. Dharavi is now more than 80 years old and to me, it’s a symbol of the failure of our society that we’ve allowed it to continue to exist in this squalid form all these decades later.

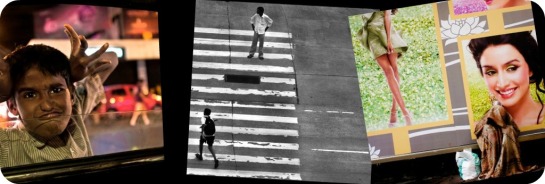

Between the Sealink and Dharavi, then, lies the whole range of Bombay clichés. We’re a city in which India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, recently built the most expensive home in the world: it cost about a billion dollars and it’s home to a family of four. We’re also a city in which about 60 per cent of the population lives in slums. In the Indian imagination, Bombay is the place where anyone with the will to work hard will never starve. But it’s also the place where children in some slum pockets face acute malnutrition, which means that they’re actually starving to death slowly. It’s the city in which everyone has the space to dream of becoming rich, but in which actual space is at a terrible premium, given that about 20,000 of us are packed into each square kilometre. (By contrast, London has a density of about 4,600 people a square kilometre.)

With typical Bombay swagger, we’ve come to celebrate all these distortions and we’re pretty smug about our ability to survive the daily grind in the place Suketu Mehta called the Maximum City. But all of this worries me a great deal. It’s apparent that Bombay has always been the barometer for the rest of India. If Bombay sneezes today, you know India will get a cold tomorrow, they say.

Over the past century, some of the most powerful ideas to influence India were born in Bombay. The very idea of India was born here when the Indian National Congress held its first meeting here in 1885, the first Indian trade union movement was born here in 1890. Since the 1930s, Bollywood has been pumping celluloid dreams into the heartland, suggesting that any adversity can be overcome if you work hard enough — and dance around a tree in the appropriate fashion.

Since liberalisation, though, the Bombay dream has changed. Where the movies once celebrated the communitarian space of the Marine Drive promenade, our film makers now showcase gated communities and malls. The self-help institutions that we once prized are being replaced by lotteries that promise to make you rich overnight. If this is the way Bombay and India are heading, I believe that the future is a little more uncertain that it’s projected to be.

It’s clear that the jarring contrasts you see everywhere in Bombay are a concrete manifestation of this neo-liberal economic model we’re flogging so desperately. If there’s one lesson Bombay teaches us, it’s that the future of cities can’t be left to the whims of market forces. It seems apparent that, despite the caution in the Western academy against the problems of what’s described as overplanning, there’s no alternative to strong regulation to ensure the public good.

I wish I could be more optimistic, but for now, things in Bombay are going pretty badly. Almost every day over the past few months has brought news of yet another real-estate scandal, in which developers have colluded with corrupt politicians and bureaucrats to make extortionate profits from public resources. Though some citizens groups are trying to resist, the odds against them seem overwhelming.

And yet, of course, life goes on. Every few days, when yet another scandal has broken, I take a walk by the promenade here to catch my breath and take stock of things. Most often, the rocks on the shore are filled with courting couples. Since space is so tight in this city, couples, even married couples, are forced to grab moments of privacy in full public view. They shelter behind colourful umbrellas to talk and grab a kiss and remind us that, no matter how bleak the world seems to be, there’s no reason for normal life to grind to a halt.

In fact, they often get so absorbed in each other that the tide sometimes rises around them and the fire brigade has to be called in to rescue them. This happens so often that, a few months ago, the authorities mounted bells across the coast and they’re sounded when the water begins to rise. To me, that’s come to represent the madness of Bombay. The water’s swelling fast and bells are clanging but we can’t hear them because we’re all too busy having a bit of fun. I wonder how it’s all going to end.

– Naresh Fernandes

Editor, Time Out Magazine